New California Court for the Mentally Ill Tests a State’s Liberal Values

By Tim Arango

Tim Arango interviewed judges, public defenders, mental health advocates and families of those suffering from severe mental illness.

When LaVonne Collette’s adult daughter, Tamra, needed a place to stay during the pandemic after being evicted, Ms. Collette let her live in a rental property she owns in Los Angeles not far from Venice Beach. That didn’t go well.

Tamra began hoarding, stuffing the house with clothing and other items collected from charities. Ms. Collette saw signs of drug use and growing paranoia, and Tamra said she believed she was living among ghosts.

“She was telling me that my house was haunted and showing me pictures, and I would hear her screaming,” said Ms. Collette, who recounted her daughter’s behavior in documents filed in court.

Sensing in 2022 that the situation would only worsen, Ms. Collette asked her daughter to leave the house and bought her an R.V., in which she lived for a time near a creek on the west side of Los Angeles. That was better, Ms. Collette figured, than her daughter living in a tent or cardboard box. But the troubles continued. Last year, Tamra carjacked her mother outside a convenience store, her mother said in the court documents.

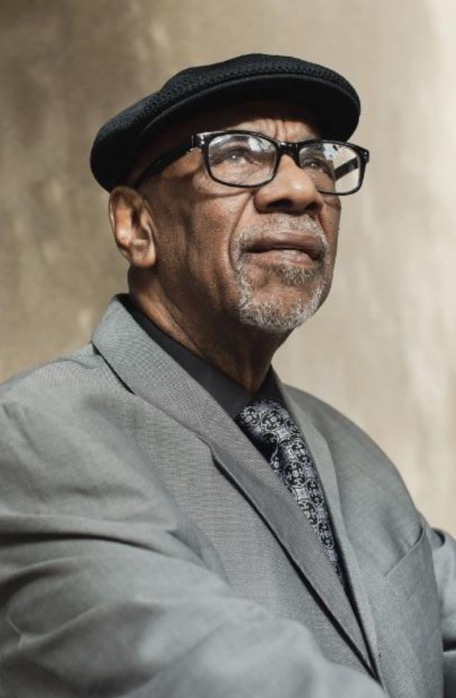

So when Ms. Collette, 68, saw news reports last year about a new state program that allows families to go to court to get treatment for loved ones who may be living in tent encampments and suffering from mental illnesses like schizophrenia, she found herself at the courthouse door as one of the first petitioners in Los Angeles.

So when Ms. Collette, 68, saw news reports last year about a new state program that allows families to go to court to get treatment for loved ones who may be living in tent encampments and suffering from mental illnesses like schizophrenia, she found herself at the courthouse door as one of the first petitioners in Los Angeles.

“I believe that if she is not helped she’s going to die,” Ms. Collette wrote in the court filing. “And she is only 41 and she has a son who loves her and mom and brother who loves her.”

The new initiative, called CARE Court — for Community Assistance, Recovery and Empowerment — is a cornerstone of California’s latest campaign to address the intertwined crises of mental illness and homelessness on the streets of communities up and down the state.

Another piece of the effort is Proposition 1, a ballot measure championed by Gov. Gavin Newsom and narrowly approved by California voters this month. It authorizes $6.4 billion in bonds to pay for thousands of treatment beds and for more housing for the homeless — resources that could help pay for treatment plans put in place by CARE Court judges.

And Mr. Newsom, a Democrat in his second term, has not only promised more resources for treatment but has pledged to make it easier to compel treatment, arguing that civil liberties concerns have left far too many people without the care they need.

CARE Court is Mr. Newsom’s bid to balance the very public and very political problem of homelessness with profound questions about individual rights in a country that for generations forced people with severe mental illness into dangerous, dysfunctional institutions.

Under Gov. Ronald Reagan, California led the country in a national movement to end widespread practice of committing the mentally ill to state institutions. But like the rest of the country, the state didn’t ensure that adequate resources were shifted to community services.

Mr. Newsom, in signing the legislation that set up the new courts, nodded to this history, calling it California’s “original sin.”

That failure helped seed the crisis that plays out in city after city.

The state’s growing homeless population — just over 180,000 people, according to federal statistics, more than a quarter of the nation’s homeless — has city parks and spaces underneath freeway overpasses bulging with encampments, and those clearly in mental distress are a common sight in communities up and down the state.

“Continue to do what you’ve done, and you’ll get what you’ve got,” Mr. Newsom said when he signed the CARE Court legislation. “And look what we’ve got. It’s unacceptable.”

View the rest of the article here